What’s stopping organizations from switching to a 4 day work week? From the financial costs to the potential culture clashes, here are the potential barriers to the four day working week.

April 5, 2022

Future of Work

Wellbeing

Leadership

Showing up to work five days a week is so ingrained it’s hard to imagine anything else - yet not working on Saturdays and Sundays is still a fairly recent invention. US carmaker Henry Ford popularised the shorter working week in the 1920s, and a new normal was born. But a century later, does the five-day or 40-hour week still work for us? Let’s dive into some of the biggest challenges for companies looking to implement a 4 day work week.

The United Arab Emirates adopted a four-and-a-half-day working week in 2021. Countless other countries - Spain, Scotland and Belgium among them - are trialling working fewer hours without dropping pay or productivity.

Many employers are ahead of the curve on this. In 2021, Atom bank became Britain’s largest company to adopt a four-day week, moving from 37 to 34 hours. When Toyota described in 2015 how it had shifted to a 30-hour week in Sweden, it had already been in place for 12 years.

The potential benefits can be profound. Toyota asked employees to work six hours a day but continued to pay them for eight - resulting in shorter customer waiting times, better productivity and low employee turnover. And when they built a new facility geared towards the six-hour day they were able to make it much smaller despite hiring more people, because the workforce was now spread across two shifts.

The reported benefits cascade further, from better employee mental health (and reduced absence) to a smaller carbon footprint and lower overheads. But there can be significant challenges to implementing a four-day week.

When it concluded in 2017, a two-year trial involving 68 nurses at an old people’s home in Gothenburg was deemed too expensive to roll-out regionally. The experiment created jobs and reduced sick pay yet cost the city 12 million Kroner (£1.1m) in extra staff.

Not surprisingly, the cost implications vary by sector. At New Zealand finance company Perpetual Guardian, staff feedback identified a need for investment into remote work tech and automation (i.e., chat bots).

US company Wildbit moved to a permanent four-day week in 2017. They’ve invested in its success by paying staff to create remote environments suitable for deep focus and quality work.

Online coding school Treehouse started life in 2013 with the 32-hour week as standard. By 2016 they’d gone the other way - to a 40-hour week.

CEO Ryan Carson has explained why the four-day week didn’t work for Treehouse, saying ultimately it contributed to a reduced work ethic. This aligns with Perpetual Guardian, where managers found increased productivity depended on whether employees saw the new model as a privilege or a right.

How the world is embracing the four-day week

The United Arab Emirates adopted a four-and-a-half-day working week in 2021. Countless other countries - Spain, Scotland and Belgium among them - are trialling working fewer hours without dropping pay or productivity.

Many employers are ahead of the curve on this. In 2021, Atom bank became Britain’s largest company to adopt a four-day week, moving from 37 to 34 hours. When Toyota described in 2015 how it had shifted to a 30-hour week in Sweden, it had already been in place for 12 years.

The potential benefits can be profound. Toyota asked employees to work six hours a day but continued to pay them for eight - resulting in shorter customer waiting times, better productivity and low employee turnover. And when they built a new facility geared towards the six-hour day they were able to make it much smaller despite hiring more people, because the workforce was now spread across two shifts.

The reported benefits cascade further, from better employee mental health (and reduced absence) to a smaller carbon footprint and lower overheads. But there can be significant challenges to implementing a four-day week.

1. The financial costs of switching

When it concluded in 2017, a two-year trial involving 68 nurses at an old people’s home in Gothenburg was deemed too expensive to roll-out regionally. The experiment created jobs and reduced sick pay yet cost the city 12 million Kroner (£1.1m) in extra staff.

Not surprisingly, the cost implications vary by sector. At New Zealand finance company Perpetual Guardian, staff feedback identified a need for investment into remote work tech and automation (i.e., chat bots).

US company Wildbit moved to a permanent four-day week in 2017. They’ve invested in its success by paying staff to create remote environments suitable for deep focus and quality work.

2. Productivity

Online coding school Treehouse started life in 2013 with the 32-hour week as standard. By 2016 they’d gone the other way - to a 40-hour week.

CEO Ryan Carson has explained why the four-day week didn’t work for Treehouse, saying ultimately it contributed to a reduced work ethic. This aligns with Perpetual Guardian, where managers found increased productivity depended on whether employees saw the new model as a privilege or a right.

3. Culture clash

It may sound counterintuitive, but not everyone wants more free time. Perpetual Guardian and Wildbit report some staff were uncomfortable with extra unstructured or alone time (Wildbit facilitates conversations about volunteering and hobbies to support this).

High demand and seasonal work can be a challenge, too, with some staff at Perpetual Guardian working compressed rather than fewer hours, i.e., gruelling 10-hour days.

Toyota’s responses include letting employees choose whether to work fewer hours, increasing the work force and introducing overlapping shifts. There are solutions – though they reveal the complexities of switching.

4. Doing things differently

In Iceland, all public employees - from office workers to nurses and police – moved to shorter hours following years of large-scale testing. Reduced hours clearly can work across diverse sectors, but it means rethinking work priorities.

Meetings can be disruptive to deep work, not to mention time-heavy. Iceland ‘paid for’ its drop to 35 hours by pruning them back in favour of email.

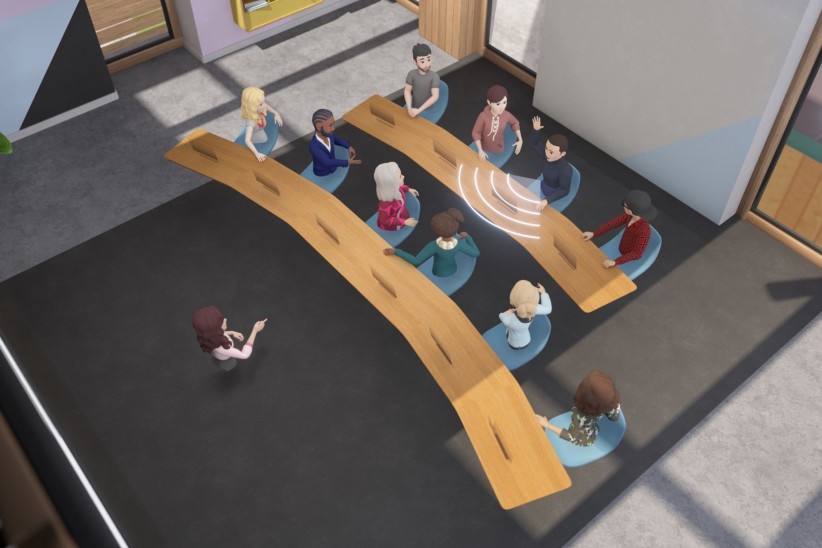

Wildbit champions asynchronous communication (email, Slack and Basecamp), though they acknowledge the social risks of losing face-to-face contact. They also underline the duality of digital tools as both productivity and procrastination enablers: they have to be used with purpose to be effective.

Organisations also need to plan how reduced hours align with leave allowances and training sessions, and how or if colleagues communicate between shifts (some Icelandic employees said the need to contact colleagues ‘out of hours’ increased with fewer hours).

When Henry Ford embraced a shorter working week he foresaw its correlation to productivity. The near universal uptake of the five-day week as standard proves his instincts were right. So is the four-day week the next logical step? The many countries and companies thriving on shorter hours is a compelling signpost - and their candour about what works and doesn't work is a useful starting point for anyone considering following suit. But changing has very real consequences on the way businesses structure their staff and their interactions with each other and clients. These complexities should be considered properly.